Understanding mCSPC

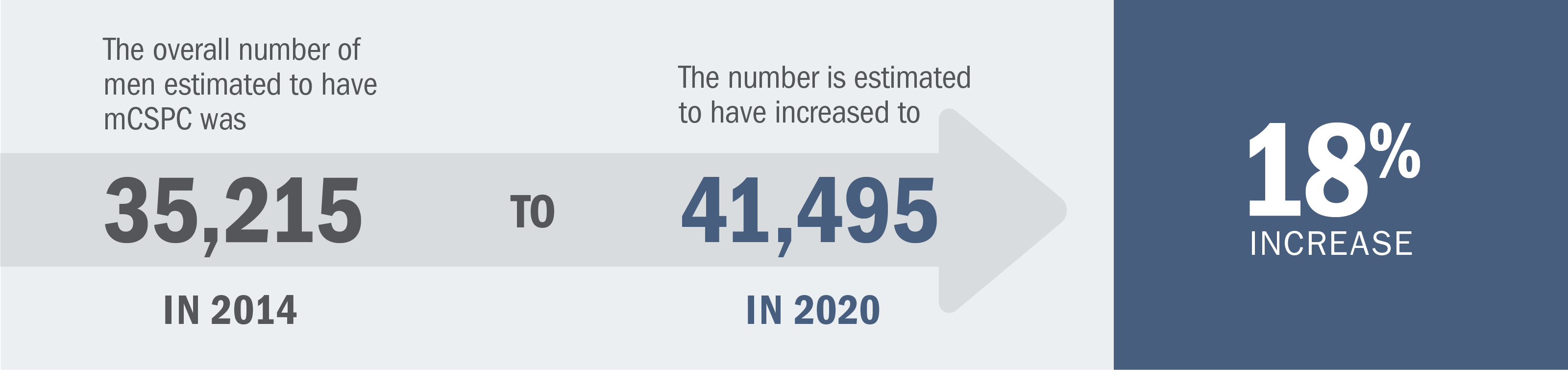

Patients may present with, or progress to, mCSPC, which is rising in prevalence.

In a projection based on SEER data1:

Based on a forward-looking model that used the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program age-specific prostate cancer incidence rate data from 2008 to estimate prostate cancer incidence for each year from 2009 to 2020. To validate the model, the final results were compared with published estimates of prostate cancer incidence and prevalence in the United States for 2009 and 2020. The model estimates for the year 2020 are based on existing/current (2009) disease incidence, diagnosis, and treatment patterns, and reflect demographic changes in the US population over time (e.g., the impact of the baby boomer population).2

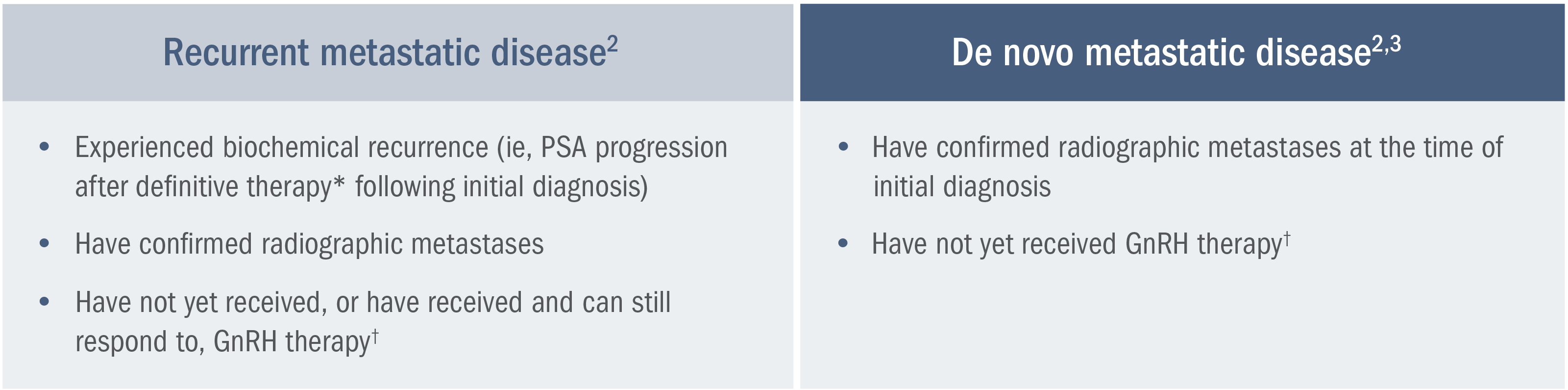

Patients with mCSPC can be diagnosed with one of the following:

*Definitive therapy is defined as a radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy with curative intent.2

†Or after bilateral orchiectomy.2

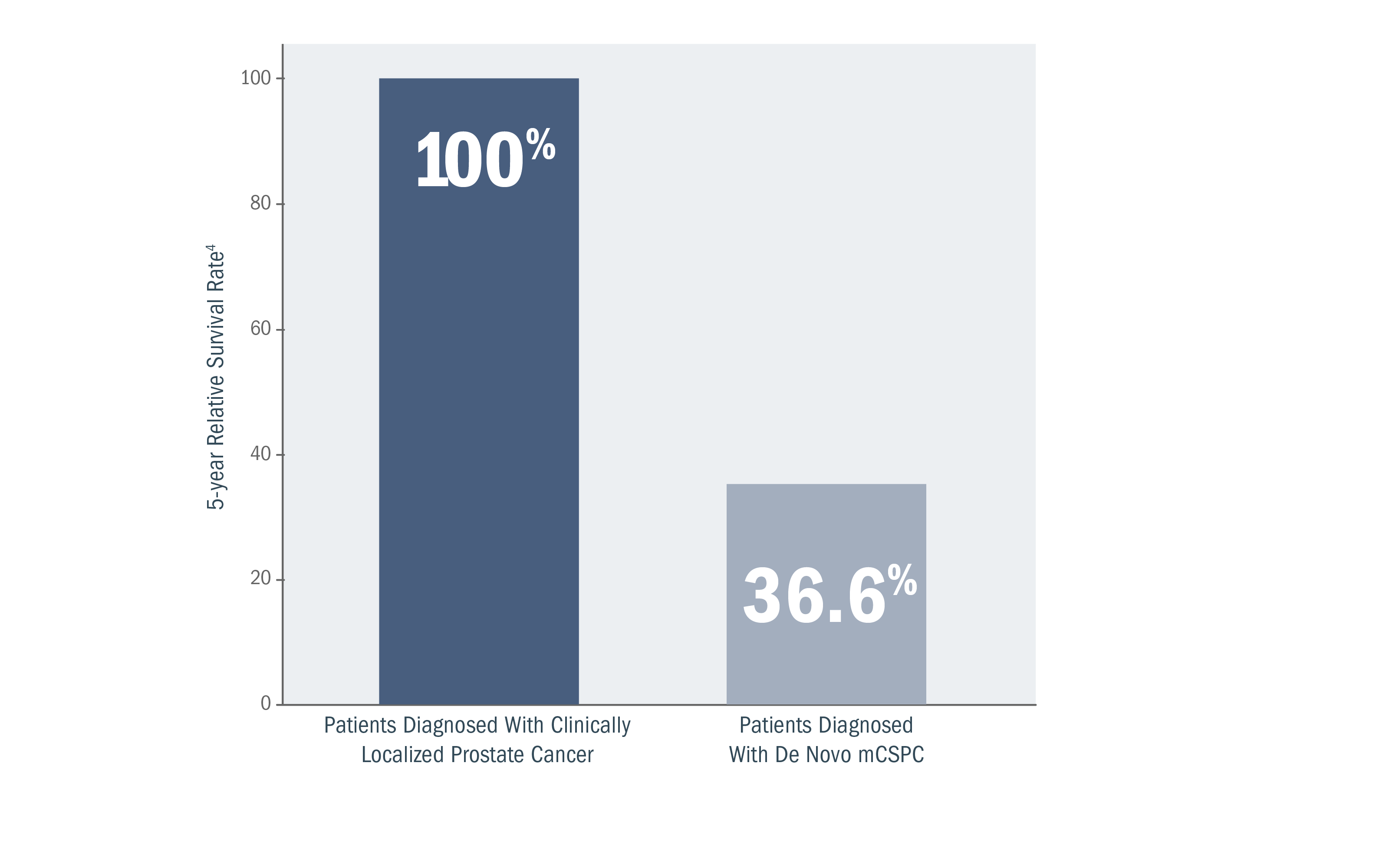

Patients with de novo mCSPC are estimated to have a lower relative survival rate than patients with clinically localized disease.4

A SEER analysis* estimates a lower (37.9%) 5-year relative survival rate for patients with mCSPC vs those with clinically localized prostate cancer (100%).4

*A retrospective analysis of SEER database, a collection of cancer incidence and survival data from population-based cancer registries covering approximately 45.9%, per anchored support of the US population, was conducted between 2015 and 2021.4,5

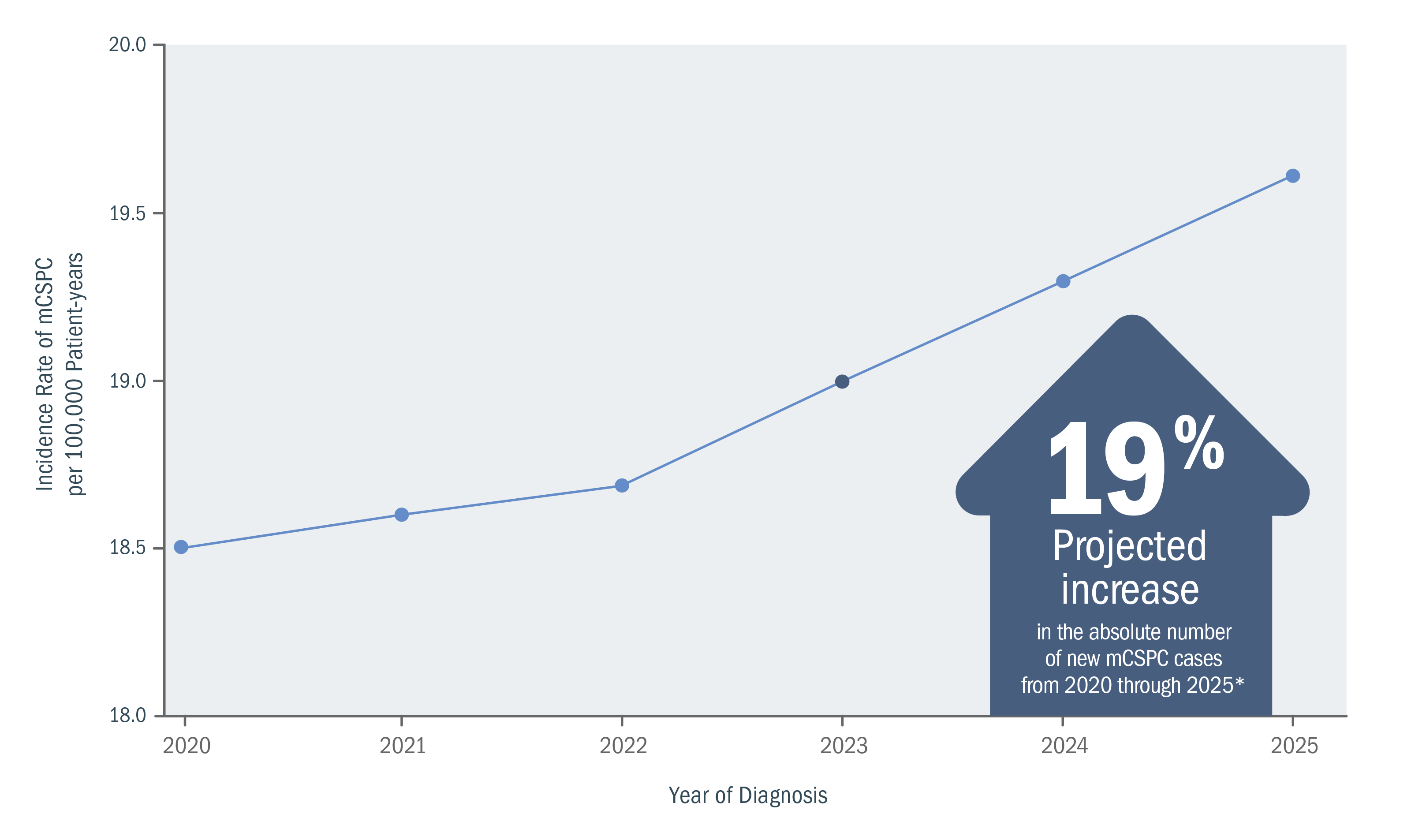

Newly diagnosed mCSPC cases in the United States are projected to continue increasing.6,7

Annual projected (2020-2025) incidence of newly diagnosed mCSPC.6,7

*From a 2018 study, based on age-period-cohort models and population projections of incidence data for men aged 45-94 years who were diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer at initial clinical presentation. Estimates were based on the population-based SEER Program registries (2004-2014).6

Understanding the mechanism of disease (MOD) and implications in nmCSPC with high-risk BCR, mCSPC, and CRPC.

Mechanism of Disease

GnRH therapy and prostate cancer cell adaptation

In response to GnRH therapy, prostate cancer cells may adapt so that androgen receptor signaling continues to drive cell growth8-12

See how XTANDI may be able to help patients with mCSPC

View Trial ResultsUnderstanding nmCSPC with biochemical recurrence (BCR) at high risk for metastasis

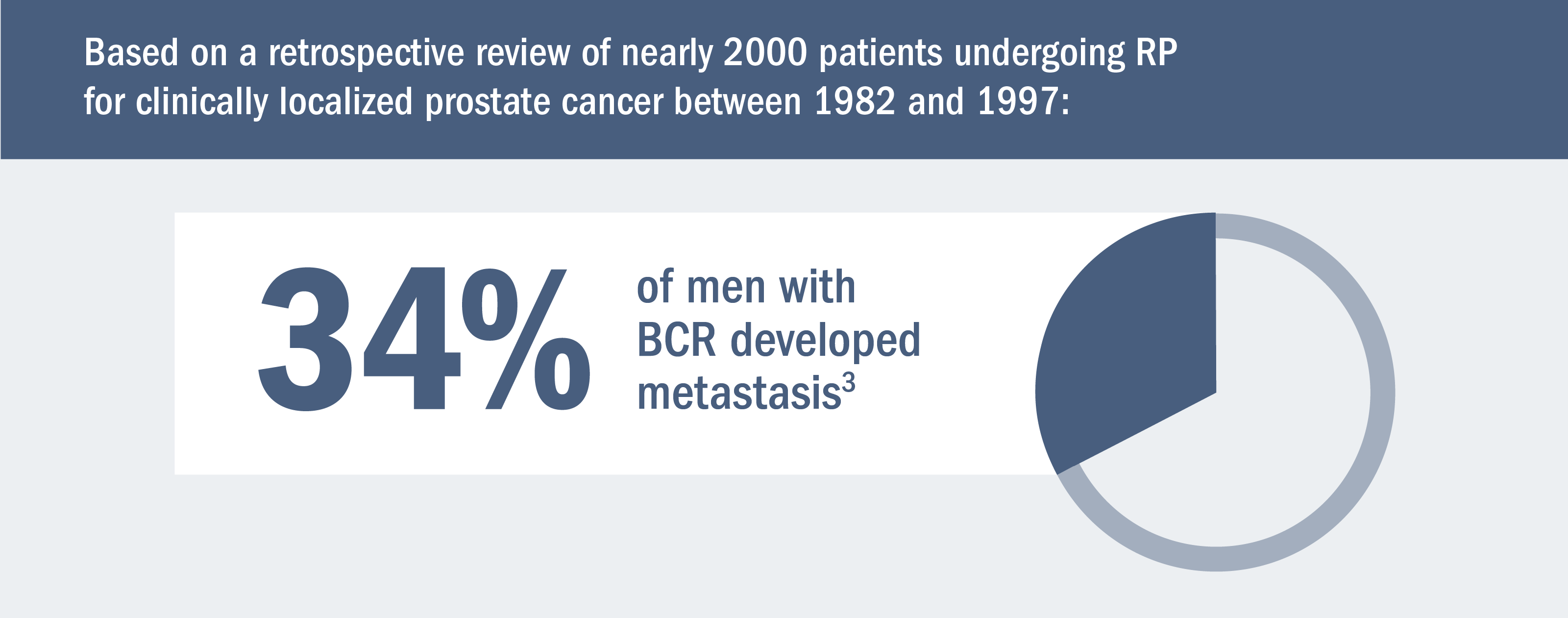

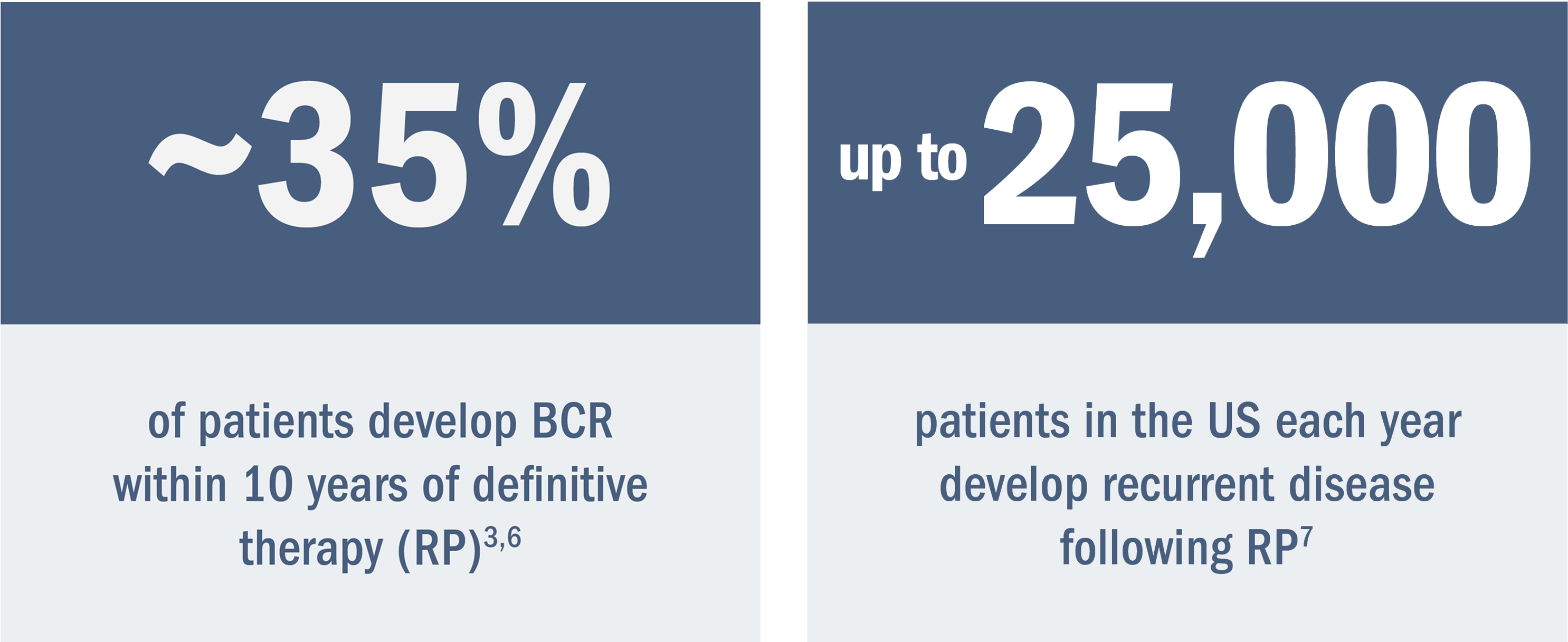

Risk for metastasis remains even after definitive therapy.*1,2

Some men may develop metastasis after definitive local therapy with radical prostatectomy (RP) or radiation (RT).1,2

*Treatment for localized disease.

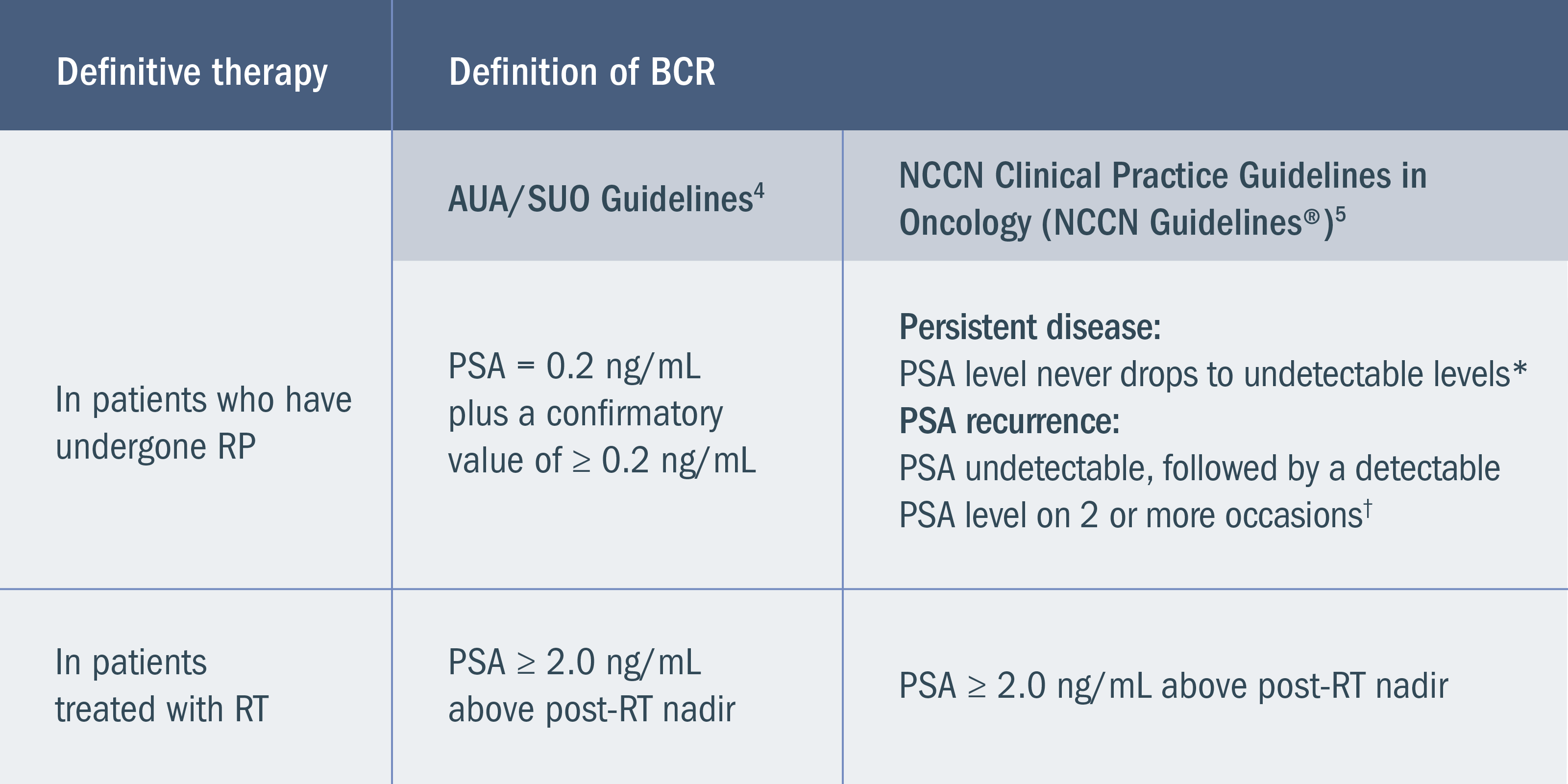

BCR is defined by rising PSA without macroscopically detectable disease after the failure of definitive therapy.4

BCR may occur in patients who do not have symptoms. The definition of BCR is based on the type of prior definitive therapy, and guidelines vary slightly between the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) and American Urological Association (AUA)/Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO)4,5:

Based on 2 retrospective studies (n = 1997 and n = 304) as well as estimates of men with preoperative high-risk disease, rates of RP, and rates of BCR3,6,7:

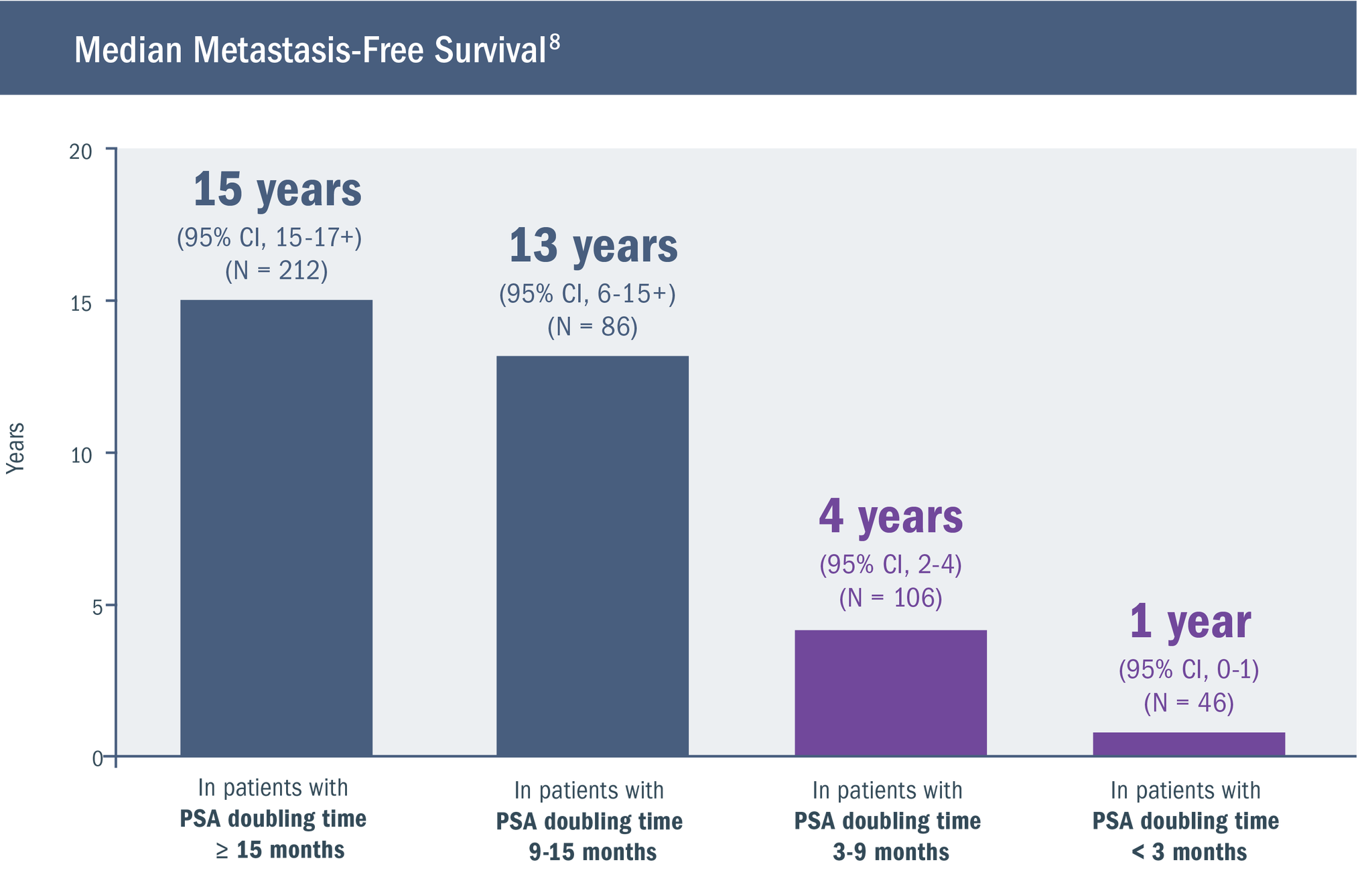

Shorter PSA doubling time is associated with increased risk for metastasis.4,6,8

At the time of BCR in nmCSPC, PSA doubling time has been shown to be one of the most reliable indicators of the risk for further disease progression. A PSA doubling time of < 9 months has been associated with poor prognosis.8-10

Based on a retrospective analysis of men treated with RP at a single hospital6,8:

- While patients with local recurrence have a PSA doubling time of 13 months, those with a PSA doubling time of 3 months present with distant metastases11

- The number of patients in the above study was relatively small, requiring that the findings be viewed as preliminary8

Watch a video in which Dr. Jason Efstathiou discusses the impact of high-risk BCR on prostate cancer prognosis.

Identifying patients with nmCSPC with high-risk BCR is an early step in prognosis and guiding the management approach3,14

Guidelines recommend monitoring PSA levels after definitive treatment.5

Following treatment with curative intent for localized prostate cancer, serial PSA measurements with clinical evaluation can be important during follow-up. These measurements enable the determination of PSA doubling time, which is a reliable indicator of the risk for disease progression.4-6,9,10

The options recommended for PSA testing by the NCCN Guidelines® for Prostate Cancer are5:

Patients at high risk of recurrence:

Every 3 months

Other patients: Every 6 to 12 months

The NCCN Guidelines suggest the option of considering tumor stage, Gleason score, and initial PSA when determining if a patient is at high risk of recurrence.5

In this video, Dr. Daniel Petrylak discusses monitoring patients for high-risk BCR.

See Dr. Evan Goldfischer review profiles of 3 hypothetical patients with high-risk BCR

Understanding the mechanism of disease (MOD) and implications in nmCSPC with high-risk BCR, mCSPC, and CRPC.

Mechanism of Disease

GnRH therapy and prostate cancer cell adaptation

In response to GnRH therapy, prostate cancer cells may adapt so that androgen receptor signaling continues to drive cell growth.15-19

See how XTANDI may be able to help patients with nmCSPC with high-risk BCR

View Trial ResultsCRPC, castration-resistant prostate cancer; CSPC, castration-sensitive prostate cancer; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; mCSPC, metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer; nmCSPC, nonmetastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

References: 1. Suardi N, Porter CR, Reuther AM, et al. A nomogram predicting long-term biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2008;112(6):1254-1263. doi:10.1002/cncr.23293. 2. Klusa D, Lohaus F, Furesi G, et al. Metastatic spread in prostate cancer patients influencing radiotherapy response [published online March 3, 2021]. Front Oncol. 2021. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.627379/full. 3. Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, Chan DW, Pearson JD, Walsh PC. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 1999;281(17):1591-1597. doi:10.1001/jama.281.17.1591. 4. Lowrance W, Dreicer R, Jarrard DF, et al. Updates to advanced prostate cancer: AUA/SUO guideline (2023). J Urol. 2023;209(6):1082-1090. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003452. 5. Referenced with permission from the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Prostate Cancer V.5.2026. © National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2026. All rights reserved. Accessed January 26, 2026. To view the most recent and complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way. 6. Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, et al. Risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2005;294(4):433-439. doi:10.1001/jama.294.4.433. 7. Dess RT, Morgan TM, Nguyen PL, et al. Adjuvant versus early salvage radiation therapy following radical prostatectomy for men with localized prostate cancer [published online June 6, 2017]. Curr Urol Rep. 2017. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11934-017-0700-0. 8. Antonarakis ES, Feng Z, Trock BJ, et al. The natural history of metastatic progression in men with prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy: long-term follow-up. BJU Int. 2012;109(1):32-39. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10422.x. 9. Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Penson DF, Fine J. Validation of increasing prostate specific antigen as a predictor of prostate cancer death after treatment of localized prostate cancer with surgery or radiation. J Urol. 2004;171(6 Pt 1):2221-2225. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000124381.93689.b4. 10. Ward JF, Blute ML, Slezak J, Bergstralh EJ, Zincke H. The long-term clinical impact of biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer 5 or more years after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2003;170(5):1872-1876. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000091876.13656.2e. 11. Hancock SL, Cox RS, Bagshaw MA. Prostate specific antigen after radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a reevaluation of long-term biochemical control and the kinetics of recurrence in patients treated at Stanford University. J Urol. 1995;154(4):1412-1417. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(01)66879-4. 12. Antonarakis ES, Chen Y, Elsamanoudi SI, et al. Long-term overall survival and metastasis-free survival for men with prostate-specific antigen-recurrent prostate cancer after prostatectomy: analysis of the Center for Prostate Disease Research National Database. BJU Int. 2011;108(3):378-385. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09878.x. 13. Freedland SJ, Sutter ME, Dorey F, Aronson WJ. Defining the ideal cutpoint for determining PSA recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2003;61(2):365-369. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(02)02268-9. 14. Han M, Partin AW, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, Epstein JI, Walsh PC. Biochemical (prostate specific antigen) recurrence probability following radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2003;169(2):517-523. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000045749.90353.c7. 15. Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):33-39. doi:10.1038/nm972. 16. Holzbeierlein J, Lal P, LaTulippe E, et al. Gene expression analysis of human prostate carcinoma during hormonal therapy identifies androgen-responsive genes and mechanisms of therapy resistance. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(1):217-227. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63112-4. 17. Attard G, Swennenhuis JF, Olmos D, et al. Characterization of ERG, AR and PTEN gene status in circulating tumor cells from patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(7):2912-2918. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3667. 18. Taplin ME, Bubley GJ, Shuster TD, et al. Mutation of the androgen-receptor gene in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(21):1393-1398. doi:10.1056/NEJM199505253322101. 19. Linja MJ, Savinainen KJ, Saramäki OR, Tammela TLJ, Vessella RL, Visakorpi T. Amplification and overexpression of androgen receptor gene in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61(9):3550-3555. 20. Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324(5928):787-790. doi:10.1126/science.1168175. 21. Bubendorf L, Kononen J, Koivisto P, et al. Survey of gene amplifications during prostate cancer progression by high-throughput fluorescence in situ hybridization on tissue microarrays. Cancer Res. 1999;59(4):803-806. Erratum in: Cancer Res. 1999;59(6):1388. 22. Koivisto P, Kononen J, Palmberg C, et al. Androgen receptor gene amplification: a possible molecular mechanism for androgen deprivation therapy failure in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57(2):314-319. 23. Richards J, Lim AC, Hay CW, et al. Interactions of abiraterone, eplerenone, and prednisolone with wild-type and mutant androgen receptor: a rationale for increasing abiraterone exposure or combining with MDV3100. Cancer Res. 2012;72(9):2176-2182. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3980. 24. Zhao XY, Malloy PJ, Krishnan AV, et al. Glucocorticoids can promote androgen-independent growth of prostate cancer cells through a mutated androgen receptor. Nat Med. 2000;6(6):703-706. Erratum in: Nat Med. 2000;6(8):939. doi:10.1038/76287. 25. Veldscholte J, Ris-Stalpers C, Kuiper GG, et al. A mutation in the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor of human LNCaP cells affects steroid binding characteristics and response to anti-androgens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173(2):534-540. doi:10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80067-1. 26. Libertini SJ, Tepper CG, Rodriguez V, Asmuth DM, Kung HJ, Mudryj M. Evidence for calpain-mediated androgen receptor cleavage as a mechanism for androgen independence. Cancer Res. 2007;67(19):9001-9005. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1072. 27. Hu R, Dunn TA, Wei S, et al. Ligand-independent androgen receptor variants derived from splicing of cryptic exons signify hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(1):16-22. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2764. 28. Dehm SM, Schmidt LJ, Heemers HV, Vessella RL, Tindall DJ. Splicing of a novel androgen receptor exon generates a constitutively active androgen receptor that mediates prostate cancer therapy resistance. Cancer Res. 2008;68(13):5469-5477. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0594.

References: 1. Supplement to: Scher HI, Solo K, Valant J, Todd MB, Mehra M. Prevalence of prostate cancer clinical states and mortality in the United States: estimates using a dynamic progression model [published online October 13, 2015]. PLoS One. 2015. Accessed Accessed April 15, 2024. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0139440&type=printable. 2. Scher HI, Solo K, Valant J, Todd MB, Mehra M. Prevalence of prostate cancer clinical states and mortality in the United States: estimates using a dynamic progression model [published online October 13, 2015]. PLoS One. 2015. Accessed April 15, 2024. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0139440&type=printable. 3. Finianos A, Gupta K, Clark B, Simmens SJ, Aragon-Ching JB. Characterization of differences between prostate cancer patients presenting with de novo versus primary progressive metastatic disease. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16(1):85-89. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2017.08.006. 4. National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: prostate cancer. Accessed July 25, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. 5. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER). Published July 2025. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://seer.cancer.gov/about/factsheets/SEER_Overview.pdf. 6. Kelly SP, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Cook MB. Past, current, and future incidence rates and burden of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4(1):121-127. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2017.10.014. 7. Supplement to: Kelly SP, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Cook MB. Past, current, and future incidence rates and burden of metastatic prostate cancer in the United States. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4(1):121-127. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2017.10.014. 8. Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):33-39. doi:10.1038/nm972. 9. Holzbeierlein J, Lal P, LaTulippe E, et al. Gene expression analysis of human prostate carcinoma during hormonal therapy identifies androgen-responsive genes and mechanisms of therapy resistance. Am J Pathol. 2004;164(1):217-227. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63112-4. 10. Attard G, Swennenhuis JF, Olmos D, et al. Characterization of ERG, AR and PTEN gene status in circulating tumor cells from patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(7):2912-2918. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3667. 11. Taplin ME, Bubley GJ, Shuster TD, et al. Mutation of the androgen-receptor gene in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(21):1393-1398. doi:10.1056/NEJM199505253322101. 12. Linja MJ, Savinainen KJ, Saramäki OR, Tammela TLJ, Vessella RL, Visakorpi T. Amplification and overexpression of androgen receptor gene in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61(9):3550-3555. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2017.08.006. 13. Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324(5928):787-790. doi:10.1126/science.1168175. 14. Bubendorf L, Kononen J, Koivisto P, et al. Survey of gene amplifications during prostate cancer progression by high-throughput fluorescence in situ hybridization on tissue microarrays. Cancer Res. 1999;59(4):803-806. Erratum in: Cancer Res. 1999;59(6):1388. 15. Koivisto P, Kononen J, Palmberg C, et al. Androgen receptor gene amplification: a possible molecular mechanism for androgen deprivation therapy failure in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57(2):314-319. 16. Richards J, Lim AC, Hay CW, et al. Interactions of abiraterone, eplerenone, and prednisolone with wild-type and mutant androgen receptor: a rationale for increasing abiraterone exposure or combining with MDV3100. Cancer Res. 2012;72(9):2176-2182. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3980. 17. Zhao XY, Malloy PJ, Krishnan AV, et al. Glucocorticoids can promote androgen-independent growth of prostate cancer cells through a mutated androgen receptor. Nat Med. 2000;6(6):703-706. Erratum in: Nat Med. 2000;6(8):939. doi:10.1038/76287. 18. Veldscholte J, Ris-Stalpers C, Kuiper GG, et al. A mutation in the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor of human LNCaP cells affects steroid binding characteristics and response to anti-androgens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173(2):534-540. doi:10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80067-1. 19. Libertini SJ, Tepper CG, Rodriguez V, Asmuth DM, Kung HJ, Mudryj M. Evidence for calpain-mediated androgen receptor cleavage as a mechanism for androgen independence. Cancer Res. 2007;67(19):9001-9005. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1072. 20. Hu R, Dunn TA, Wei S, et al. Ligand-independent androgen receptor variants derived from splicing of cryptic exons signify hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(1):16-22. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2764. 21. Dehm SM, Schmidt LJ, Heemers HV, Vessella RL, Tindall DJ. Splicing of a novel androgen receptor exon generates a constitutively active androgen receptor that mediates prostate cancer therapy resistance. Cancer Res. 2008;68(13):5469-5477. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0594.